On my morning walk yesterday, something clicked. I was thinking about an upcoming concert I’m organizing for a friend—a singer, with hired musicians, mp3s to learn from—and I found myself anticipating all the little moments where things wouldn’t be perfect. Where someone would need help navigating a tricky change. Where the band would need to function as a safety net, not just a backing group.

That’s when I remembered the phrase: hand holding.

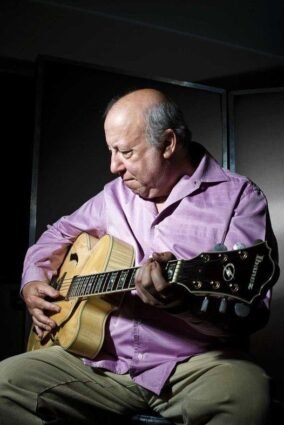

Not in a condescending way. More like the quiet, generous act of helping someone—or being helped—through a tune in real time. And as I walked, I realized something odd: in 50 years of playing guitar and 15 years of serious jazz study, I’d never heard anyone actually talk about this.

The Silent Skills We Never Name

We talk endlessly about scales, voicings, comping patterns, and phrasing. We analyze solos, transcribe lines, and work through Real Books. But the subtle art of keeping the music together when things aren’t perfect? That lives in the shadows.

Yet it’s happening constantly. Visual cues—a nod, eye contact, the angle of your guitar neck pointing toward the next section. Physical signals—a bassist’s head bob on beat one, a pianist’s shoulders lifting before a key change. And musical cues—walking up chromatically to telegraph where we’re going, voicing a turnaround more clearly when you sense someone’s lost, creating tension that signals release is coming.

This is the connective tissue of live performance, especially in jazz where so much happens in the moment. But somehow, it’s treated as something you just “pick up along the way” rather than a skill worth discussing, let alone teaching.

Two Moments That Brought This Home

The concert prep was one trigger. I’ve hired good musicians, and I’ll send them charts and recordings. But I know from experience they won’t have every tune locked down perfectly. Someone will miss a turn. Someone will hesitate at a bridge. And in those moments, the band needs to be ready—not to judge, but to guide.

The second moment was more recent. I was playing with a drummer—a great drummer—who’s lost some hearing after decades of loud gigs. I found myself instinctively adjusting. Playing with a more defined tone. Making my phrasing more obvious. Not dumbing things down, but creating clearer landmarks for him to navigate by.

“Playing with a more defined tone. Making my phrasing more obvious. Not dumbing things down, but creating clearer landmarks to navigate by.”

And as I did this, I realized: nobody taught me this. I learned it by playing with people who did it for me when I needed it. By watching how generous players supported the music rather than just showing off their own skills. By being rescued, and eventually learning to rescue others.

Taking the Risk

After that walk, I felt like I’d stumbled onto something worth discussing. So I posted about it in the private study space my jazz tutor runs—a forum where his students share ideas and experiences.

I’ll be honest: I was nervous. Sticking your head above the parapet always feels vulnerable, especially when you’re naming something that doesn’t seem to have a name. What if everyone thought, “Well, obviously—why are you even bringing this up?” What if nobody responded at all?

But I posted it anyway. Described the hand holding concept, the two situations that prompted it, and asked if anyone else had thoughts on this unspoken aspect of playing together.

The Response That Validated Everything

My tutor’s response was better than I could have imagined. He called it “a really perceptive observation” and said I was right—it’s almost never taught explicitly. He wrote:

“What you’re describing is musicianship beyond notes. It’s the quiet language that keeps the music moving when things aren’t perfect—which, of course, is most of the time in real playing situations.”

He loved the phrase “hand holding” because it captured the spirit perfectly. Not control. Not correction. Support.

Then he added something that really hit home: “That’s not ‘dumbing things down.’ That’s taking responsibility for the music.”

When I adjusted my playing for the drummer with hearing loss, I wasn’t compromising my musicianship—I was using it in service of the collective result. That’s a fundamental shift in perspective: from “what do I want to play?” to “what does the music need right now so we can stay together?”

“That’s not ‘dumbing things down.’ That’s taking responsibility for the music.”

Living in the Cracks

My tutor explained why this skill rarely gets taught: it lives in the cracks between the things we do teach. It’s not theory. It’s not technique. It’s not repertoire. It’s awareness.

You learn it by playing with people, making mistakes, being rescued, rescuing others, and slowly realizing—as he so beautifully put it—that “clarity is kindness on the bandstand.”

Think about the moments that stay with you. Someone walking you into a bridge with a clear bass line. A pianist playing a louder chord on beat one when they sense you’re drifting. A horn player shaping a phrase so clearly that the form suddenly makes sense again. Those aren’t flashy moments. They’re generous ones.

What This Means for How We Play

After 50 years of playing, I’m still discovering layers to this craft. And what strikes me about this particular insight is how fundamental it is. We spend so much time developing our individual voice—our tone, our vocabulary, our improvisational chops—but jazz is ultimately a conversation. And in any good conversation, you’re not just expressing yourself; you’re listening, responding, and sometimes gently guiding.

The players who keep the music together aren’t necessarily the ones with the fastest fingers or the hippest lines. They’re the ones who:

- Play with clearer phrasing when needed

- Create more obvious harmonic motion at crucial moments

- Maintain a stronger time feel to anchor everyone else

- Use slightly exaggerated cues in sound and body language

These aren’t tricks or shortcuts. They’re acts of musical leadership and care.

Still Learning After All These Years

What keeps jazz endlessly fascinating—even after five decades—is that there’s always another layer to discover. Just when you think you’ve got a handle on the music, you realize there’s this whole dimension of unspoken communication you’ve been participating in without fully seeing it.

My tutor suggested this could be an ongoing conversation in the study group, because while we may not be able to “teach” it in the traditional sense, we can learn to notice it, name it, and value it.

I think he’s right. And I think it starts with recognizing that supporting your fellow musicians—hand holding, if you will—isn’t a beginner skill you outgrow. It’s an advanced form of musicianship that deepens the more you do it.

The next time you’re on the bandstand and you catch yourself walking up to a change more obviously, or nodding toward the turnaround, or voicing that chord progression a little more clearly—recognize what you’re doing. You’re not holding the music back. You’re holding it together.

And that might be the most important thing we do.

Have you experienced moments of musical hand holding—either giving or receiving support on the bandstand? How do you think about this unspoken dimension of playing together? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.